Why the rise of blockchain games means the end of loot boxes

Patrick Barile on the implications of the new ownership model

Given the nascent state of blockchain gaming, we’re keen to highlight as many interesting industry viewpoints as possible.

Patrick Barile is VP, Partnership at Flexion Mobile and a keen observer of the blockchain space. This is the first column in what we hope will be a regular series.

Of course, his views are his own, and shouldn’t be taken as representative of his employer or BlockchainGamer.biz.

According to industry predictions, the games industry – already growing healthily – will enjoy another significant boost as it adopts blockchain technologies.

On a decentralized open ledger, everybody can check if virtual goods have been created and assigned. Possession becomes transparent.

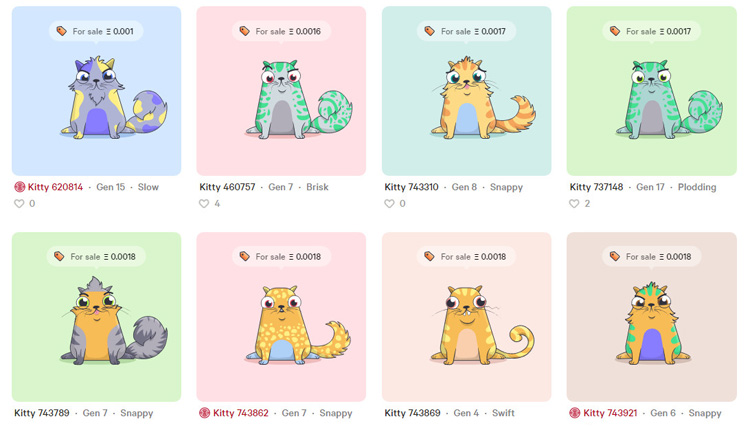

Many different approaches in terms of how games can benefit from the blockchain are being contemplated and one particular use case stands out: the ‘Blockchainification’ of in-game virtual goods.

Even though virtual goods have enjoyed wide adoption and commercial success, the drawbacks have been a lack of clear ownership and transferability.

This means that players, in most cases, cannot sell their virtual goods.

This is a problem the blockchain should be able to address. By storing the purchase of a virtual good on a decentralized open ledger, legitimate ownership becomes provable. Players would be empowered to transfer and trade goods among each other.

Enforceable ownership enables scarcity

Today, virtual goods can be created by their issuers (the game developers) at will and at scale.

In free markets, inflating the supply of goods leads to a price decrease. The blockchain is therefore a great tool for game developers to create and market ‘limited edition’ virtual goods in a credible way.

On a decentralized open ledger, everybody can check if virtual goods have been created and assigned. Possession becomes transparent. Therefore, developers can limit supply in a credible way and ensure downward price stability.

For players, ‘limited edition’ therefore really means ‘limited edition’.

In the coming years players can brace themselves for a flood of such rare virtual goods hitting the market, and game developers won’t let such a juicy revenue opportunity pass by.

Risks and rewards

Assuming these obvious benefits for players and developers, the remaining question to answer is, how can we integrate tradeable virtual goods into a game?

Let’s look at a couple of options

- 1. Players can purchase tradable virtual goods

Selling tradeable virtual goods should be straightforward, meaning a developer offers a tradeable virtual good and the player acquires it, knowing they’ll be able to sell it on at a later point in time.

The whole thing might get tricky, however, when we talk about tradeable virtual goods in limited editions. If demand is higher than the number of goods on offer, the developer has to decide how to award the limited goods. First come, first serve? By auction? By chance?

If the developer chooses the latter and on top asks the player to pay for being included in the distribution by chance (without guaranteeing allocation) is getting into very risky territory. This might get classified in countries like the US as gambling.

- 2. Player get tradeable virtual goods by chance

The distribution of tradeable virtual goods by chance should in most cases and most countries be simple, but as mentioned above, things might get difficult if payments are required for being included in such distribution by chance.

A classic example for such case might be loot boxes or gacha. The player buys more and more loot boxes hoping to get a limited edition virtual item but without any guarantees. There’s a considerable risk such case being categorized as gambling in the US.

A game qualifies as gambling if all three of the following criteria are satisfied:

- a game has to have an element of chance

- the player must give up something in order to play

- there needs to be a prize or item of value at stake

In the past, developers such as Machine Zone (Game of War) and IGG (Castle Clash) have escaped lawsuits by having had virtual goods not classified as items of value under gambling statutes. Such an assessment might change, if a virtual good becomes tradeable thanks to a decentralized ledger aka the blockchain.

- 3. Player get tradeable virtual goods by skill

Let’s assume a player obtains a tradeable virtual good by their individual skill or capabilities to master a game. Let’s also assume the valuable good can be sold at a later point in time and the player had to pay for participating.

Such a setup might leave the developer of the game in a legal grey area. Skill-based gaming involving payments are banned in some countries but not in others. In the US this varies on a state by state level.

Conclusion

Yes, the ’Blockchainification’ of virtual goods offers tremendous opportunities for the game industry. However, similar to the discussion about loot boxes the whole story gets tricky once players are asked to pay up and there’s an element of chance or skill involved.

When offering tradeable virtual goods, developers won’t be able to hide behind the missing item of value (gambling criterium #3). The value obtained from tradeable virtual goods can be measured and cashed out.

This should mean game over for loot boxes on the blockchain. It will force developers to be clear about their offering: is it a gambling like experience they want to offer?

Developers will have to think hard on how to distribute tradeable virtual goods. On the positive side, this might be an opportunity for the gaming industry to come clean and differentiate itself clearly from the gambling industry.

Don’t forget to follow BlockchainGamer.biz on Twitter and Facebook.